Zebulon

Details

- Date

- May 22, 2024

- Venue

- Zebulon Los Angeles, California

- Billed As

- Robyn Hitchcock

- Gig Type

- Concert

- Guests

- Kelley Stoltz, Pete Strauss, Rusty Miller, Luther Russell

Notes

Originally billed as "Robyn performs his favourite songs from 1966 + 1967" (original poster in images)

Later changed to a repeat of Robyn's Syd Barrett show previously performed in San Francisco in January

Drums/Percussion - Kelley Stoltz

Bass - Pete Straus

Keyboards/Guitar - Rusty Miller

12 String Guitar - Luther Russell

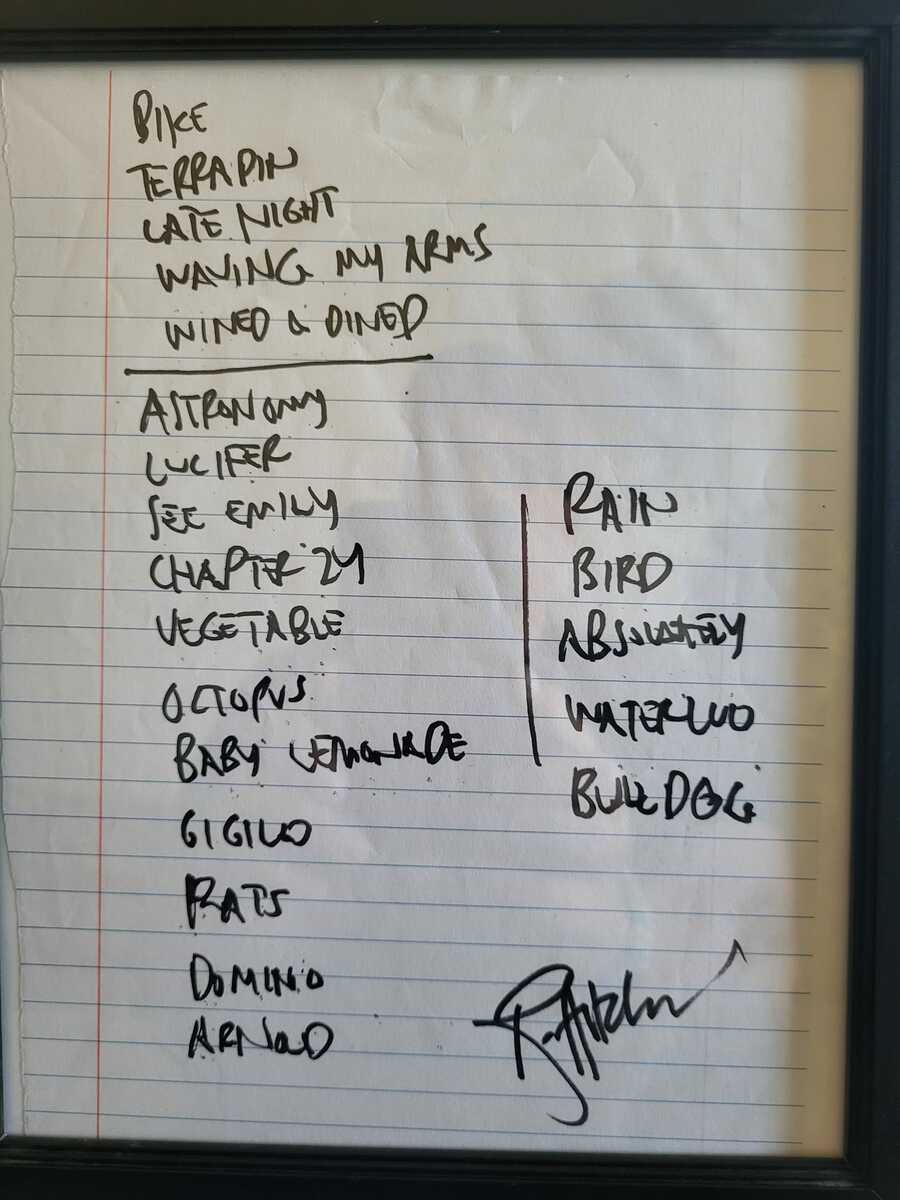

Setlist provided by Hyacinthe R

Setlist photo by Moe G

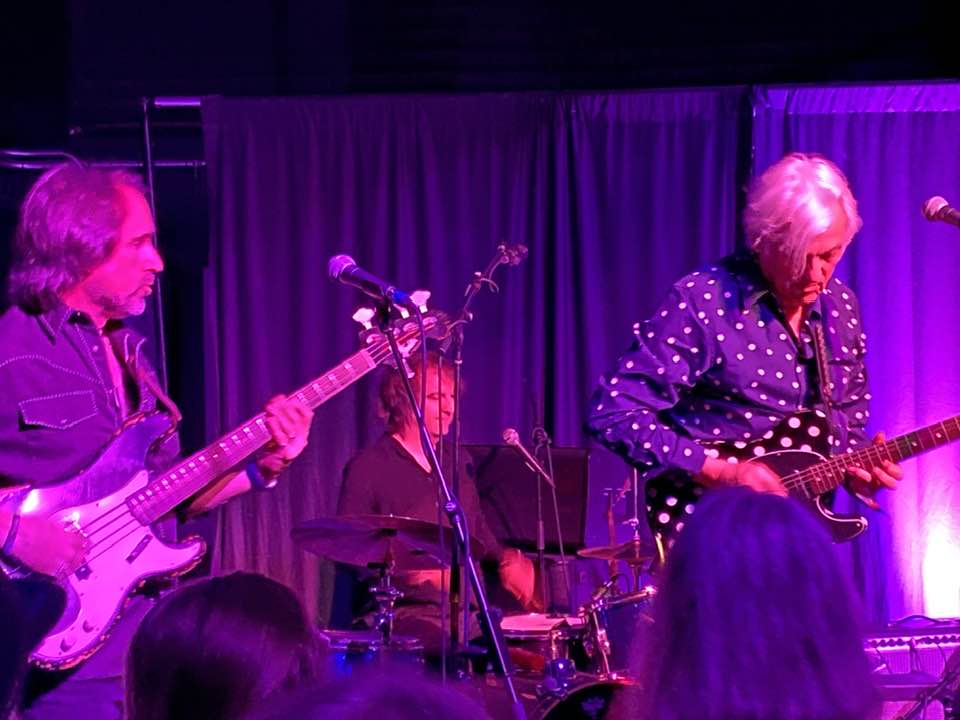

Live photo by Jordan O

Later changed to a repeat of Robyn's Syd Barrett show previously performed in San Francisco in January

Drums/Percussion - Kelley Stoltz

Bass - Pete Straus

Keyboards/Guitar - Rusty Miller

12 String Guitar - Luther Russell

Setlist provided by Hyacinthe R

Setlist photo by Moe G

Live photo by Jordan O

Set List

-

Terrapin

Syd Barrett solo acoustic

-

Bike

Pink Floyd solo acoustic

-

Late Night

Syd Barrett solo acoustic

- If It's In You Syd Barrett solo acoustic

- Waving My Arms in the Air Syd Barrett solo acoustic, segues into

- I Never Lied to You Syd Barrett solo acoustic

- Wined and Dined Syd Barrett acoustic, with Rusty Miller

- Long Gone Syd Barrett acoustic, with Rusty Miller

-

Astronomy Domine

Pink Floyd

- Lucifer Sam Pink Floyd

-

See Emily Play

Pink Floyd

- Chapter 24 Pink Floyd

-

Vegetable Man

Pink Floyd

- Octopus Syd Barrett

-

Baby Lemonade

Syd Barrett

- Gigolo Aunt Syd Barrett

- Rats Syd Barrett

- Dominoes Syd Barrett

-

Arnold Layne

Pink Floyd

- Interstellar Overdrive Pink Floyd

Encore

- Rain The Beatles

- And Your Bird Can Sing The Beatles

- Absolutely Sweet Marie Bob Dylan

- Waterloo Sunset The Kinks

- Hey Bulldog The Beatles

Media

Video of complete performance. Full band set first, acoustic set at end

Alternate video of complete performace

video of Wined and Dined and Long Gone

Reviews

Online review by Independent Review Crew (note show date in review is incorrect)

In the end, Pink Floyd was a gigantic rock band. But before that, under founder Syd Barrett, it was a deep and dark vision. The band’s debut album The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967), written almost entirely by Barrett, veers from whimsical melodies to acid-fueled freak-outs — and casts a shadow over the illustrious run that would follow, after Barrett infamously “lost his mind” and was forced out of the group.

There are chilling reports of Barrett onstage detuning his guitar strings one by one, frozen, stranding the band to cover for its leader. Or of him teaching them a new song, but secretly changing its complicated chords each rehearsal, mind-fucking them: “Have you got it yet?” And there is continued debate: Did LSD cause the breakdown? Was Barrett predisposed to psychosis? Was his catatonia a revolt against music business pressures? At some point, Barrett ceased verbal communication with anyone outside his immediate family, a near-silence that continued until his death in 2006.

The songs survive as compressed gems in two ways: not only did Barrett create them during a very brief period (barely a year from the first singles, “See Emily Play” and “Arnold Layne,” through that first album), but they also subsume vast styles and subjects — fairy-tale melodies of bikes, gnomes, and magical cats (“Lucifer Sam”), trips through cosmic chasms (“Interstellar Overdrive” and “Astronomy Domine”), and the I Ching (“Chapter 24”).

Barrett’s creativity and descent into madness have long haunted songwriter and rocker Robyn Hitchcock. Like his idol, the younger Hitchcock began exploring music in Cambridge and London. Among his bands were the Soft Boys, and projects spanning power pop, psychedelia, punk, and folk from the 1970s to today. Throughout, he has immersed himself in Barrettology.

In a Q Magazine interview, Hitchcock said: “Syd went beyond being an influence to points where there’d be a takeover. […] It was quite sinister. It was as if at certain times when I was singing or writing it was no longer me but this other guy. There were times when I thought ‘My God, this guy is roosting in my head.’”

Hitchcock’s Zebulon performance on Tuesday, May 21, celebrated this uncanny merging. Starting his set solo with acoustic guitar, Hitchcock then welcomed band members to render the woven melodies and progressions loosely yet true to form. For audience Syddites, it was pure wish fulfillment: early Floyd resurrected. They even facsimiled the cosmos of “Interstellar Overdrive.” The original studio recording is a deceptively improvised 10-minute instrumental. But unlike the extended space jams of later Pink Floyd, the gravitational pull of this piece is dense with fleeting, glitching, intricate passages and concentric colors. At its black-hole core, under Zebulon’s op-art light swirls, a possessed Hitchcock intoned lyrics of his own.

The encore consisted of five more cover songs from around 1967: three Beatles numbers plus the Kinks’ “Waterloo Sunset” and Bob Dylan’s “Absolutely Sweet Marie.” A fitting finale, since on June 28, Little, Brown (UK) and Akashic Books (US) will publish Hitchcock’s memoir, 1967: How I Got There and Why I Never Left.

In the end, Pink Floyd was a gigantic rock band. But before that, under founder Syd Barrett, it was a deep and dark vision. The band’s debut album The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967), written almost entirely by Barrett, veers from whimsical melodies to acid-fueled freak-outs — and casts a shadow over the illustrious run that would follow, after Barrett infamously “lost his mind” and was forced out of the group.

There are chilling reports of Barrett onstage detuning his guitar strings one by one, frozen, stranding the band to cover for its leader. Or of him teaching them a new song, but secretly changing its complicated chords each rehearsal, mind-fucking them: “Have you got it yet?” And there is continued debate: Did LSD cause the breakdown? Was Barrett predisposed to psychosis? Was his catatonia a revolt against music business pressures? At some point, Barrett ceased verbal communication with anyone outside his immediate family, a near-silence that continued until his death in 2006.

The songs survive as compressed gems in two ways: not only did Barrett create them during a very brief period (barely a year from the first singles, “See Emily Play” and “Arnold Layne,” through that first album), but they also subsume vast styles and subjects — fairy-tale melodies of bikes, gnomes, and magical cats (“Lucifer Sam”), trips through cosmic chasms (“Interstellar Overdrive” and “Astronomy Domine”), and the I Ching (“Chapter 24”).

Barrett’s creativity and descent into madness have long haunted songwriter and rocker Robyn Hitchcock. Like his idol, the younger Hitchcock began exploring music in Cambridge and London. Among his bands were the Soft Boys, and projects spanning power pop, psychedelia, punk, and folk from the 1970s to today. Throughout, he has immersed himself in Barrettology.

In a Q Magazine interview, Hitchcock said: “Syd went beyond being an influence to points where there’d be a takeover. […] It was quite sinister. It was as if at certain times when I was singing or writing it was no longer me but this other guy. There were times when I thought ‘My God, this guy is roosting in my head.’”

Hitchcock’s Zebulon performance on Tuesday, May 21, celebrated this uncanny merging. Starting his set solo with acoustic guitar, Hitchcock then welcomed band members to render the woven melodies and progressions loosely yet true to form. For audience Syddites, it was pure wish fulfillment: early Floyd resurrected. They even facsimiled the cosmos of “Interstellar Overdrive.” The original studio recording is a deceptively improvised 10-minute instrumental. But unlike the extended space jams of later Pink Floyd, the gravitational pull of this piece is dense with fleeting, glitching, intricate passages and concentric colors. At its black-hole core, under Zebulon’s op-art light swirls, a possessed Hitchcock intoned lyrics of his own.

The encore consisted of five more cover songs from around 1967: three Beatles numbers plus the Kinks’ “Waterloo Sunset” and Bob Dylan’s “Absolutely Sweet Marie.” A fitting finale, since on June 28, Little, Brown (UK) and Akashic Books (US) will publish Hitchcock’s memoir, 1967: How I Got There and Why I Never Left.